VPA/FLEGT

VPA/FLEGT is a Voluntary Partnership Agreement on Forest Law Enforcement, Governance and Trade signed between the EU and Vietnam. The FLEGT processes use a strong consultation process that involves all stakeholders to promote forest governance for all actors by enhancing the rule of law and managing natural resources. In general, timber sources from production forests are facing two problems, namely (1) difficulties in determining the origin of timber and (2) lack of legal evidence to determine that transactions in the supply chain are legitimate

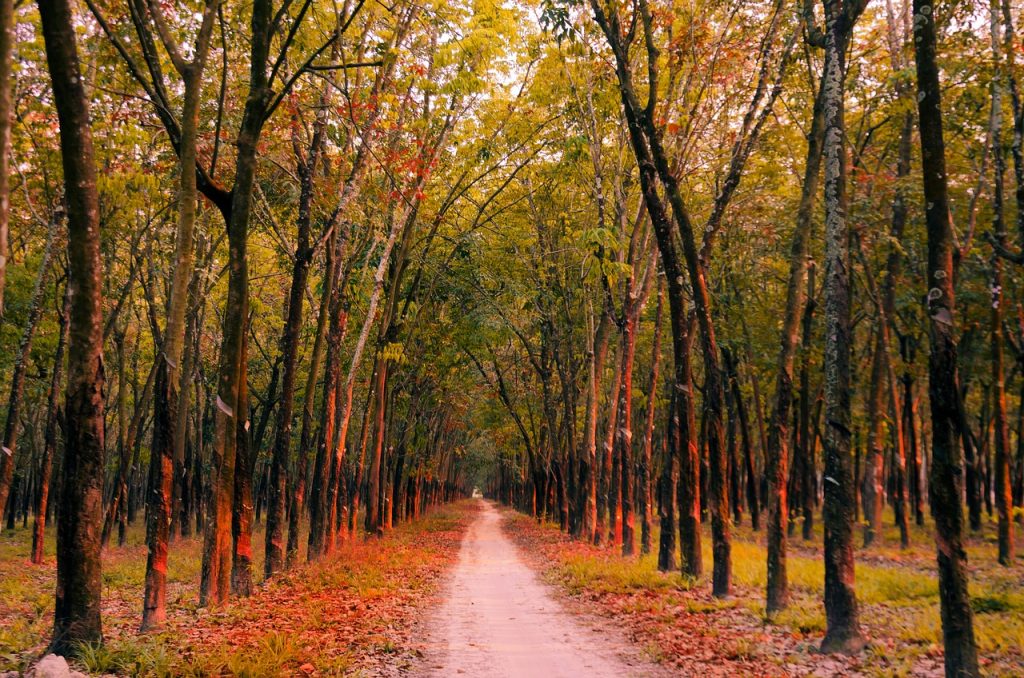

(1) Difficulties in determining the origin of timber occur because the areas of land where the timber is harvested lack legal evidence to determine that the timber-selling households have full legal ownership rights to the area (To and Cam, 2022). The legality of timber produced by these rubber smallholders varies greatly due to the type of land used for growing and the availability of evidence proving the legality of land and timber. Most rubberwood grown by smallholders poses clear legal status, proved through the land-use certificates. However, a small proportion of 10-20 % of rubberwood poses unclear legal status, because these households have not yet received the land-use certificates from the Government due to bureaucracy constraints (NEPCON and Forest Trends, 2018). Land use certificates are important legal documents to prove legal status to forestland holders. Without these documents, forest owners cannot prove their right to the land. In addition, many households have illegally converted forests into rubber plantations. This is against the regulations set out in the Forest Protection and Development Law. Thus, timber harvested from this source is considered to be of illegal origin. Rubberwood sourced from encroached areas or unregistered ownership transferration also leads to the unfulfillment of legality requirements (NEPCON and Forest Trends, 2018).

Both agricultural and forestry land is used to grow rubber trees. As a result, the commune People’s Committee is responsible for certification and verification of the legality of the wood grown on this property. On the other hand, the district’s Forest Protection Department is responsible to verify and certify rubberwood obtained from forestland. Due to the lack of data on the area of forestland and agricultural land cultivated by smallholders, there is difficulty in the verification and certification of the legality of the timber produced by smallholders (NEPCON and Forest Trends, 2018).

To verify the legality of rubberwood and lay the groundwork for certification, a comprehensive survey is required to identify the exact areas of rubber plantations being grown by smallholders on agricultural and forested land. In addition, guidelines and procedures from the government for local authorities are necessary to guide the verification of the legality of rubberwood and is a good foundation for certification (NEPCON and Forest Trends, 2018).

(2) The lack of legal evidence to determine that transactions in the supply chain are legitimate. This existence occurs when the participants at the intermediary stage in the chain undertake informal activities without having fulfilled their legal responsibilities, especially tax responsibilities. For instance, the majority of transactions between local sawmills or traders and smallholders are informal. The local authorities certify very few transactions between two parties (NEPCON and Forest Trends, 2018). A study conducted by NEPCON and Forest Trends in 2018 showed that only 8 % of processing families reported having asked for and got sufficient supporting documentation to prove legality for their imported timber. Sawmills are unable to comply with timber legality criteria for a number of reasons, according to Dang Viet Quang et al (2013), including:

- Processors lack purchase documentation because household sawmills do not have tax invoices.

- Absence of employment contracts or other mechanisms to ensure workplace safety.

- The majority of sawmills lack a formal environmental protection policy.

- Challenges of determining the source of wood that has been sawn up in sawmills from several sources.

Conclusions and recommendations

Rubberwood is an important source of raw materials contributing to the development of Vietnam’s wood processing industry with more than 265,000 smallholders and more than 1,500 wood processing companies in supply-chain benefitting from the export of rubber wood (Tran, 2020). However, the majority of smallholders work independently, which limits their access to knowledge, the market, and state support. Smallholders are excluded in the process of policy formulation and implementation because of the lack of representation.

The formation and or participation of forest farmers in cooperative entities, and rubber plantation organizations would allow the group to gain a legal status which will consequently (1) attract direct cooperation and collaboration with processing enterprises due to the reduction of transaction costs, (2) increase information and market access, (3) better access to state and other sources of support (e.g. loan), (4) increase the representation and participation in the policy consultation, formulation and implementation process.

In addition, timber (such as rubberwood) is one of the seven major commodities included in the recently approved EU Deforestation Regulation as having the potential to contribute to deforestation and forest degradation. The regulation aimed to lessen the effects of the EU on global deforestation and forest degradation as well as to encourage the adoption of “deforestation-free” products. Because a small number of rubber materials and products are exported to the EU market, further research should be done to analyze the potential impacts of the new regulations on the market structure of rubberwood in Vietnam with the existence of problems in the supply chain.

References

Tô Xuân Phúc và Cao Thị Cẩm (2022). Tính pháp lý của gỗ nguyên liệu rừng trồng tại Việt Nam: Một số tồn tại và kiến nghị về chính sách. NICFI, UKaid.

Trần Thị Thúy Hoa (2020). Đánh giá Quốc gia về các nhà sản xuất và nhà máy chế biến gỗ cao su ở Việt Nam. FAO-FLEGT Programme.

NEPCon and Forest Trends (2018) Diagnoses and Regulatory Assessment of small and micro forest enterprises in the Mekong Region.

Đặng Việt Quang, Quách Hồng Nhung, Phạm Đức Thiềng, Nguyễn Thanh Tùng, Cao Thị Cẩm (2013). Xưởng xẻ gỗ hộ gia đình trong bối cảnh FLEGT-VPA [household-based sawmills in the context of FLEGT VPA]. Forest Trends, GIZ and VIFORES.

Tiếng Việt

Tiếng Việt